It’s

a funny thing coming home. Nothing changes. Everything looks the

same, feels the same, even smells the same. You realize what’s

changed is you.

F. Scott Fitzgerald

So, I was back in Winnipeg again, just three years and eight days after leaving it with little more in my head than a wish to escape the shame of my dismissal from the Canadian Army. But now my outlook was wholly transformed, owing to the plan I had to salvage something of my life.

While I was gone from home, my mother and stepfather had exchanged their ageing house in Saint Vital for a newly built one in Windsor Park, a smarter part of the town. I would reside with them till Jack and I had located a place of our own, but I was pleased when my mother invited Jack to lodge with us in the meantime.

Now, why would she put out the welcome mat for an utter stranger when, just the year before, she had given the bum’s rush to her own son? Well, Jack was of English breeding, you know, with an accent akin to hers before it was bastardised by Canadian pronunciation. And then, you know, Jack displayed a fawning manner, calculated, doubtlessly, to pacify people and lull them into trustfulness.

On my friend Larry’s suggestion, we escorted Jack to the place of Larry’s labours, Great West Life (or the Great Waste of Life, as Larry had christened it), on Osborne Boulevard, bidding him to step inside and request a job, while we, his conscientious custodians, stretched ourselves on the grass outside.

Great West Life Building, Winnipeg

Conversely, I got a job slaving away at Ogilvie Flour Mills, so that while Jack was pushing a pen for his bread, I was humping sacks of flour for mine.

Ogilvie Flour Mills, Winnipeg

The exact nature of my labours at that place has faded from my memory. All I recall is one temporary task I was called upon to do. One day, I was ushered outside to the colossal side of an open railway freight wagon towering on a track at the back of the mill, from which a roller conveyor descended from a second floor opening. My precise duty there was to sweat away at the bottom of the ramp, heaving onto a shoulder sack after sack of wheat that came plummeting down the conveyor and stack them in the wagon. As each sack weighed a crushing 140 pounds, the work was criminally backbreaking. Mercifully, I was not compelled to discharge it for long.

With earnings now assured, I found Jack and I a place to lay our sleepy heads in a house on Langside Avenue.

Houses on Langside Avenue, Winnipeg

In May, I was sent an invitation to the wedding reception on June 8th of Rick Callen, a lad whose family lived on Monreith Street, where I had passed my teenage years. Although everyone new everyone else at our end of the street, we two Wingfield boys had had little to do with the two Callen lads, whose house was towards the end of the thoroughfare. We saw much more of Sandy Stalker, who lived just over the road.

Now Mrs Stalker, who lacked a husband for some reason or other, was of a rather flighty disposition. Instead of a husband to love, she had a son to adore., an adoration evident even in the way she summoned Sandy to lunch. Whereas we two Wingfields were marshalled for meals or bed with a blunt: ‘Colin - Ian!’, from the grim lips of our stepfather, our friend opposite was bidden with the entreaty: ‘Sandy, darling!’ to which the unflagging response was: ‘Coming, mother!’

A couple of incidents testify that Sandy was anything but the darling son his loving mother conceived him to be. One day, for instance, he displayed to our wondering eyes a live bat he’d got hold of somehow and kept imprisoned in a little makeshift cage. I was not very charmed when Sandy darling began jabbing the bat with a stick and watching gleefully while the creature fearfully strained to escape.

Another time, for our diversion, he got hold of his dog’s penis and began gleefully masturbating the animal.

Yes, very precocious was Sandy. But perverted might have been a better word. Once, I recall, he established an aberrant practice amongst us boys. He’d grab you by the knackers and cackle, “Check your baggage?” But once he made the mistake of grabbing the knackers of Billy, the younger Callen son, who straight away dashed indoors to bleat the business to his mother.

Moments later, Mrs Callen, an English lady, but no rose, came sweeping outside, shouting, “Who’s been grabbing my son’s balls!”

That effectively ended one manifestation of Sandy’s brashness.

But it is really Rick Callen that I am principally concerned with here, for it was through an invitation to his wedding reception in July that I met my future wife.

She was a friend of Rick’s fiancée, Sonia, and as she was the only free female at the bash, it was natural that I should gravitate towards her. Having recently returned from England, my interest was aroused at once when she answered my chatter with an English accent.

“What part of England are you from?” I wanted to know, expecting to hear the name of some place in or near London. But I was wrong.

“Liverpool,” she replied.

“Liverpool?” I said, delighted. “I’ve been there!”

I had been there, too, yes, as I described in an earlier post, with my friend, John Coakley, almost exactly three years before. And I was rapt now at having the chance to relive memories of an active and fascinating life that was now slipping insistently into the misty past.

From that day onward, Judith and I began spending evenings together, but in contrast to my earlier affairs with girls, this one was not driven by frenetic fantasies of romantic love, but was grounded from the outset in friendship and mutual sympathy. Maybe that is why, from that time onward, my inveterate awkwardness with girls began to subside.

In July I sat for the Grade XII Literature exam and waited in trepidation for the results to be despatched. I was keenly aware that my entire future depended on what was in the envelope that finally arrived at my door, so that I tore it open crazily…

I had passed!

But just by a hair. My mark was a meagre 50R.

The meaning there was that I had passed the exam on a rereading. Nothing to preen myself about, but I was not in quest of spectacular marks. This little slip of paper, flimsy as it was, represented a passport to a university degree that would redeem me from the fate of incessant drudgery at some tedious, repetitious, crushing, humdrum job that would finally snuff out every trace of life inside me.

Yes, fate was now obviously smiling upon my path. Not only was I en route to a university, but, because of the fact that my father had died as a result of the war, the Department of Veterans Affairs would pay my fees and provide me with finance for food and lodging for the duration of my studies!

But, I mused, what should I study? Well, by now I knew myself well enough to study arts rather than science, but what courses should I choose? Sadly, that old bugbear of English Literature was compulsory in the first year, but I considered I might deal with it by means of hard work. In any case, I was beginning to develop a taste for English Literature as a result of reading the works on my correspondence course. I even recognised by now that Shakespeare, whom I'd loathed in school, had an astonishing gift for framing in simple and few words lessons of life experience.

Such as, for example:

“Listen to many, speak to a few.”

or

“One may smile, and smile, and be a villain.”

I would study French, too, because I already had a grounding in it, and History, as well, because it had never been a headache for me. Finally, I would do a course in psychology, because my imagination had been stirred somewhere, somehow by the fascinating idea that people have an unconscious mind that supplements their conscious one.

At long last, the day came when I strode into the grounds of the University of Winnipeg on Portage Avenue and bore witness to the truth of my mother’s prophecy. I never did see the gates of the university because there were none!

University of Winnipeg

Of course most of my fellow students were some years younger than myself, a fact that served rather to boost my confidence, since, unlike them, I had six years of working life to my credit.

I must confess that most of the poetry offered at university made little impression on me. It was only the poets of the Romantic age that stirred my imagination... and few enough of them.

But the psychology course was a devastating disappointment. There was not a whisper of any unconscious mind because that concept and many more absorbing ones besides belonged to the realm of Freudian psychology, while the only psychology on offer here was Behaviourism, a tedious creed that – for all I could guess - tried to simplify the complexities of human behaviour by the study of rats! That told me more about the coarse-grained nature of the practitioners of this canon than about psychology.

In the spring of 1968, I bought a 1957 Volkswagen Beetle with money I borrowed from my girlfriend.

My first year at university is somewhat muddled in my memory, owing maybe to the fact that I had no clear plan of advance. However, I passed all my courses, though with unremarkable results.

I should say now that in the summer of 1967 Jack and I moved out of my parents' place into rented lodgings on Langside Street. Some months later, I moved out to join Judith in a room she was renting on Spence Street.

It was not long before Jack got chummy with my old friend Willard, and gradually disassociated himself from my life. He wormed his way into Willard’s affections to the extent that when Willard got married, he chose Jack to be best man, a choice that showed he was impervious to the claims of a long standing friendship that had permitted him to see something of the wider world. And when Jack got married, he didn’t even invite me to his wedding, only to the reception.

Thus it was that my early feelings about Jack on meeting him in England turned out to be providential. And I was reminded of Shakespeare’s linking of grinning with villainy.

McGregor Armoury, Winnipeg

At the dawn of my university life, sensing again a little nostalgia for the lures of soldierly life, I joined the Fort Garry Horse Militia Regiment at McGregor Armoury in Winnipeg. The most riveting memory of my time in the regiment was of an adventure I weathered in the dead of a bitter Manitoba winter. We were camped in tents somewhere out in a waste of snow and brittle shrub with nothing but candles for heat and light. Surprisingly, I felt warm enough at night in my regulation army sleeping bag, but I was a bit chagrined on the second day when I felt the need to relieve my bowels. I blenched at the thought of dropping my drawers in sub-zero temperatures and squatting in a ‘latrine’ fashioned from heaps of frosty snow.

But I had no choice, so it was Down trousers and undies! Do doodoos! Swab bottom! and Up undies and drawers once more! the fastest I ever effected the task before or since!

Manitoba Road in Winter

The end of my first year at university finally meant deliverance from the chains of English Literature. The only problem was that I was growing rather fond of English Literature, while my other studies left me cold. So it was that at the start of my second year I signed up for a course in 19th and 20th century English.

But as time crept by, I began to understand that it was not precisely English Literature that had claimed my allegiance, but the literature of the Romantic age. In particular, John Keats set my feelings alight with his poem Ode on a Grecian Urn

and especially with these lines:

“Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though winning near the goal, yet do not grieve;

She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss,

For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair!”

But why did these lines strike me so strongly? for my record shows that I never was a 'bold lover'. I was, on the other hand, obsessed with kissing. By means of an embrace and a kiss, I hoped to strive to the heights of human feeling. I hoped to escape the ennui of life on waves of sensation, on billows of 'bliss'.

You cannot blame me when most seek their salvation, their 'bliss', in the pursuit of money and the things it can by, while

their notion of love embraces not a lot more than plain copulation. My

ideal was at least a human one.

So, who cares what this little vase says or doesn't say? It is just a little bit of history, these sleepwalkers through life might say.

History?

“History is bunk,” said Henry Ford.

“History is little more than the register of the crimes, follies and misfortunes of mankind.” wrote Edward Gibbon, the eminent historian.

Keats said as much in the last two lines of his poem:

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty, -That is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

The time was soon coming when I would have to abandon History as a means of finding my way in life.

I think it was in this year of 1969 when the drug culture finally hit Winnipeg. I don’t think it got much purchase there because prairie people are quite conservative, though our crowd was rather more liberal and not averse at all to sampling a little cannabis, while cleaving chiefly to good old Manitoba lager. But one of our number, Fred, got enthralled with ‘smoking dope’ and made it his life's ambition to shine as a self-styled dope wallah.

It was not long before Fred graduated to LSD, for, being a high-school drop-out, that was the only kind of graduation he could conceive. But the upshot of his new renown was that one sunny winter day, several of the old crowd: Larry, Fred, Jim, Ian and I, plus a couple of girlfriends, headed east on Highway 1 for Granite Lake, just over the border in Ontario, where a cabin belonging to Larry’s family was located. Our aim was to make it the location of an initiation into LSD, conducted by Fred. Ian wasn’t keen to participate and he was backed by Fred, who suggested we would need someone to attend to us in case we got into hot water.

The women weren't party to this lark either. After trudging from the highway to the cabin and settling inside, Fred distributed the capsules and we ingested them expectantly. When the dose had taken hold, we quit the cabin, descended to the frozen lake and took to shuffling about in the vast stretch of fluffy snow cloaking the ice.

Canadian Lake in Winter

We seemed lost in a landscape dazzlingly bright, framed by an interminable fringe of jade green ranked formations of fir trees. It was a vast and striking aspect, but it didn’t have the stamp of reality as we joked and posed at an angle, ‘leaning against the scenery’. How we passed the time out there, apart from standing and staring, I don’t well recall, but I did note the drug’s effect on memory. Some foggy concept of heading somewhere would fasten itself in your head, and then set you strolling, booting a footway through the snowy desolation until the way was barred by a question: where am I going? As no passable answer was at hand, you scanned the surrounding sheet of snow and the serried ranks of trees until you decided on a different goal and strode onward in a different direction. This game was played out again and again during the day.

But my efforts to find comfort in drugs foundered on the recognition that their affect was anti-social, for under the influence of 'Weed' or 'Acid', you took little interest in other people. That estimation of things was born out later when Jim just vanished from my life.

The end of my second year at university revealed a plummeting performance attended by marks even lower than those obtained in my first year. This was worrying. What could account for the three Ds I'd got? (a D was a low pass)

Two of the Ds were distressing, but the third was staggering, because it was in English Literature, a subject that I had learned to love. By contrast, the other courses sucked the life out of me. So much so, that I had been toying with the idea of changing my ‘major’ subject from French to English. But with such a dismal record in English, did I dare to make the change?

I did.

In early 1969, Judith and I decided to marry and as a preparatory measure moved into a modern apartment block on Stadacona Street east of the Red River.

Our apartment block on Stadacona Street, Winnipeg

Now, there was just no way we fancied getting married in the common way. We wanted no priest, no church, no wedding reception, no clanging bells, just a simple civil service and a bit of a bash afterwards at my parents’ place. Thus, the humble ceremony occurred on May 2nd at the Law Courts Building on Broadway with Larry and Bonnie as witnesses,

Law Courts Building, Winnipeg

Soirée at Stranmillis Avenue

The next day, we decamped again to ‘Larry’s Cabin', which Larry kindly offered us the use of for our honeymoon.

Honeymoon at Granite Lake, Ontario

In the summer of 1969, the commandant of my militia regiment asked me if I cared to take a summer job working for the regiment. Apparently, he had wangled some cash from the Manitoba government to mount a small group of militiamen at Lower Fort Garry, an old fort some 32 miles north of Winnipeg. They would entertain visitors to the fort by marching around the grounds attired in 19th century British Army uniforms. My job would be to keep the militiamen supplied with the equipment needed to keep the show going.

I accepted.

Sometime in 1969, Jim reappeared in my life. It seems he'd wearied at last of smoking dope with Fred and annexed himself to me again. I flatter myself that it was because I had some idea of where I was going. At least I had a plan for the future. When I’d achieved my degree, I would take a teaching post for a year to save up some money and then return to England, the place where I planned to make our home. Why was I returning there? you might ask, for in England I would earn less than half the cash I could finger in Manitoba. But, as the words of the song went: “How can you keep them down on the farm after they’ve seen Parie”.

There was much to see in England, and the land was saturated with the annals of the past, an aspect that enchanted me immensely because it whispered a promise of belonging and offered a calming narcotic in the increasingly frenetic haste of modern life, at least as I perceived it in Canada and the USA. And Europe? That, too, harboured analogous magnetisms, as well as the opportunity to learn about the lives of people speaking languages different from mine.

But I had to have patience, for I was still in the land of harsh winters, and in this winter Judith and I, in company with Larry and Bonnie, made another trip to ‘Larry’s cabin’, just for something different to do and somewhere different to go.

It is fascinating to think how big things grow from small beginnings. One day in the U of W cafeteria, I got talking with a girl who was taking a course called something like The Religious Quest in the 20th Century. My hackles were raised at that, but then she said the course did not consist of any conventional study of religion, but instead analysed writings about belief. In the lesson she was about to attend, she told me, her class was exploring a story called Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad. I was a little intrigued as she related a little of its plot, and then she asked me if I would like to join her in the lecture.

I came out of it with my mind enflamed, and after getting the book and reading it, I felt I'd got hold of a chunk of fundamental wisdom about the nature of human life. And yet it was, after all, only an adventure story. But then, isn't human life an adventure of the profoundest kind? I had never met or heard of anyone who even suggested such a thing.

The story was set just before the end of the 19th century, when a man named Marlow is engaged by a French company to undertake a journey up an unnamed and lengthy river in darkest Africa to take charge of a steamboat whose captain had died of fever, and to pilot the vessel many more miles up the river to the company's innermost station to find an agent called Kurtz, who had also contracted the fever, and conduct him back to Europe.

Now this Kurtz had made of himself a very successful ivory trader, but the company wished to get rid of him because his methods for extracting ivory from an impossibly remote aria of Africa were ‘unsound’. The man, exempt from all of the checks and balances that normally hold human beings to account had turned himself into a kind of god with powers of life and death over the simple people of the region, even to the point of compelling them to perform certain ‘unspeakable rights’ in his honour.

Yes, it was a cracking yarn, all right, but more, it was a moral discourse making plain the crucial quality needed to make a success of humanity. That quality, Conrad called 'restraint', meaning a capacity to reject certain experiences as harmful to a truly human life.

And what drew me most strongly to the tail was it's arrant rejection of bourgeois society!

In my final year of study, I worked more purposefully, the reward for which was honourable marks. My Statement of Marks included this observation: STUDENT OF DISTINCTION.

As well as achieving B+ in each of my three English courses, I felt I'd acquired not only an enviable set of marks but also a means of expression. But three marks of B+ for English Literature, a subject I had repeatedly failed in the past? What could be the conceivable reason for that failure?

Well, it’s likely my working-class background was partly to blame. My mother, I know, read the odd book in bed, but she was attracted mainly by smutty stuff like The Awful Tale of Maria Monk or Peyton Place. My stepfather, by contrast, read no books at all. He would ensconce himself in bed with a bag of peanuts and a Zane Grey comic (that he had ostensibly bought for my brother and I) or a copy of the Police Gazette. I remember only once receiving a book for Christmas. It was called The Lost World of Everest, likely based on The Country of the Blind by H.G. Wells. I remember how it stirred my imagination, and I read it at least twice, but, sadly, no other books came my way.

I have no memory of seeing the inside of a library, but when I began junior high school, I discovered that once a week a lesson took place in the library, where pupils were free to choose a book and read it. I recall eyeing several rows of them. How could you choose a book without knowing what was inside it? I peeked between the covers of a couple and then sat down with a magazine. The teacher, making a round of her pupils, asked me why I wasn’t reading a book. With a blush, I muttered that I didn’t know what to read.

“What are you interested in?” she asked sympathetically.

“Well, I like animals,” I answered.

She was off then, and was back in seconds with a book called Bonny’s Boy. It was a story about a boy and his dog, and I loved it. But library lessons were not a permanent feature of the school curriculum and my interest in reading sank as fast as it had risen.

Two years later, I was compelled to study The Merchant of Venice by William Shakespeare. Merchant? Teenage boys had no interest in salesmen! What they wanted was adventure, not business! In actual fact, the school English curriculum turned me against literature. I would not be ready to read Shakespeare for another eight years!

But I was musing about the road ahead. There was just one hazard obstructing the way: to teach in Manitoba now, you had to have a certificate for the purpose, as well as a degree. Thus it was that shortly afterwards, I was tramping the hallowed halls of the University of Manitoba to complete the first part of a teaching course, the second part of which could be secured in the following summer. But I had no intention of attending next summer, because by then I’d be on my way to England’s green and pleasant land, empty of any breath of extra credentials.

The course turned out to be an excruciating test of one’s ability to suffer boredom. Is it really possible to teach anyone to teach? Maybe a good teacher could come up with a few clues, but the ones here were bunglers. I learned later that a common expression in the world of education was ‘Those who can, do, those who can’t, teach’. We sufferers of these blunderers used to say, ‘Those who can, teach, those who can’t, teach teachers’.

Jim and I endured this dismal affliction together. One of the other students was an eager female called Walleen, who was a devotee of some loony method of body stretching in search of some nonsensical nirvana. The ‘prof’ was as lazy as a slug, as well as incompetent, and one day he turned his whole group of trainee teachers over to Walleen for the purpose of exhibiting the blessings of her method of relaxation. Jim and I arrived late (as usual), and we opened the door on a flock of – what? - penitents? The floor had been cleared of desks and the penitents were gathered willy-nilly in the middle of the room with Walleen calling the shots with fervent ecstasy.

“Now stretch your arms above your head and be really high, as high as you can,” she wheezed feverishly.

The guinea-pigs surged upwards toward the ceiling, perched on tiptoes, arms stretched high.

“Now, make yourself as small as you can, really small, as small as possible.”

And the guinea-pigs plummeted to the floor, squirming into circled shapes, chins pressed to necks and fingers gripping shins.

Jim and I shared a glance of disbelief before closing the door with care and quietly stealing away.

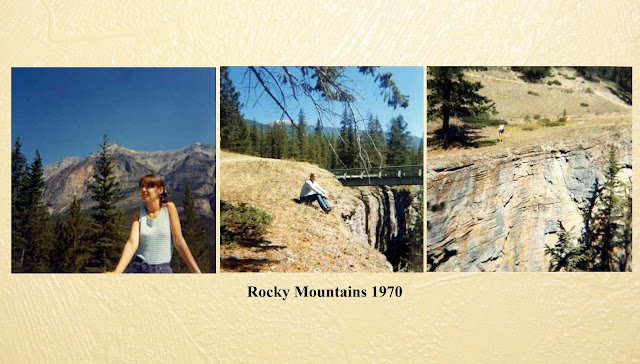

Somehow or other, Judith and I squeezed a trip to the mountains out of that summer of 1970.

My first teaching post was at the small town of McCreary, Manitoba, 250km from Winnipeg.

By a happy chance, we were able to rent a house there for the period of my teaching post.

Almost every weekend, we headed back to Winnipeg to meet friends and celebrate occasions such as Halloween.

Winter in Manitoba is long, arduous and rude, compelling human kind to seek warmth indoors and contemplate the arctic landscape outside their windows.

But even harsh winters have their charms. For a couple of days in January, the school was closed and all the pupils and teachers were driven in the school bus out to the nearby low lying Riding Mountains for a skiing expedition. Both Judith and I learned to ski there. I remember the ski lift with its single bars to sit on instead of seats, and there was a café where you could get a coffee. In the photo below, the ski run comes down from the right and the café is on the left.

Mount Agassiz Ski Resort after closure

But other, more modern, ski resorts eventually appeared, and this one closed in 2000, when the owner filed for bankruptcy. In 2014, the area of the site was 'returned to its natural state'.

Skiing apart, the quality of life in McCreary was unremittingly humdrum. So much so, that we'd spend most evenings down at the school, in company with three other teachers, where Judith typed out worksheets I had fabricated. But one evening got engrossing when two strangers entered the staffroom, one introducing the other as Ed Schreyer, no less a person than the Premier of Manitoba, the man who managed the Manitoba Government in the Manitoba Legislative Building in Winnipeg.

Ed was there, it seems, to deliver a speech to a gathering just now settling in the auditorium, and he would, if we didn't mind, said Ed's attendant, wait with us in the staffroom until the time for his speech.

Well, certainly!

The aid vanished, and we teachers just wriggled and sniffed a bit until I came up with a question to ask our honoured guest. I can't remember the question, nor can I recall the reply, or the rest of the talk that followed, but at least a clumsy silence was avoided. England had taught me some manners!

When Ed had left to deliver his speech, Wilf, a fellow teacher, stated his amazement that I had treated our guest just as though he were 'an ordinary guy'. Well, he was an ordinary guy. I don't think I've ever met an extraordinary one.

By this time, my brother Ian and friends Larry and Jim had all married,

To make the journey more engaging, I planed to travel by train from Winnipeg to Montreal, and then board a ship for Liverpool. Ian and Jim approved the plan, but Larry opted to fly from Winnipeg to London, where we would meet him.

Thus it was, that in the first week of July 1971, we six eager globetrotters boarded a train at Union Station in Winnipeg,

and went the way my girlfriend had gone seven years before.

After traversing 1,132 miles of train track mainly buried in Ontario forest, we slowed to a screeching halt in Montreal Quebec.

I'm afraid to say that we did not find the city very welcoming, owing, we supposed, to the reluctance of its inhabitants to speak English to us. We spent one night in a Montreal hotel and the next day went down to the docks, where we boarded the Empress of Canada,

which soon was sailing down the Saint Lawrence River on its way to the Atlantic Ocean.

Saint Lawrence River

I no longer recall what day it was in July 1971 when we sailed into the Port of Liverpool, but the Empress of Canada was definitively retired from service on the 9th of November of that year.

This exhilarating arrival at the docks in Liverpool signalled the end of my wandering life. Two years later, the three couples accompanying my wife and I had gravitated back to Canada. But we two remained in England for another 44 years.

Liverpool Docks

For the next story, click on the appropriate link:

No comments:

Post a Comment