Published: 20.11.2020

Jacob van Ruisdael’s Windmill at Wijk bij Buurstede, his most famous painting, and his masterpiece Two Undershot Water Mills with an Open Sluice are the centrepieces of his wind- and water mills works. Both types are man-made devices that depend on forces of nature for their operation, but their use in the Netherlands and their place in seventeenth-century Dutch art differ greatly.

In Ruisdael’s day windmills were everywhere in his native land. Then, as now, they were the best-known symbol of the Dutch landscape. Ruysdael drew them first as a teenager and then to his very last years. Like many others, he depicted all types of windmills in various settings. By contrast water mills were scarce. They were found only in a very small area in the new Dutch Republic’s eastern provinces, particularly in the region near the border between the Netherlands and Germany. Ruisdael discovered the possibilities they offered for his art on a trip there in the early 1650s. He was the first artist to think of making a water mill the principle subject of a landscape. Apart from Meindert Hobbema, his only documented pupil, hardly a handful of Dutch artists made use of the idea he invented.

Meindert Hobbema: The Travelers

But whether they used it or not, it has proved very endearing. The English landscape artist, John Constable wrote to his best friend on the very day he saw a Ruisdael water mill in a London dealer’s shop: “It haunts my mind and clings to my heart”.

John Constable: Param Mill, Gillingham c1826

Jacob van Ruisdael, the pre-eminent and by far the most versatile seventeenth-century Dutch landscapist, made a number of surprisingly varied and original paintings and drawings of windmills. They were done at a time when people were keenly aware of their deep dependence on the forces of nature that run such mills, an awareness that happily has been resuscitated in our time: heightened interest in renewable energy has led to construction worldwide of enormous electric power-generating turbines, whose forebears were windmills.

Curiously enough, in my first job as an adolescent I had to work on the repair of one of the generators shown above that had broken down at Slave Falls, Manitoba. (See my post on that experience.)

Ruisdael’s choice of windmills as a motif in landscape settings is easy to understand. In his day, thousands of them whirled their sails in the Netherlands. Some provided energy needed to pump water out of lakes, marshes and low-lying land and to drain it away via canals at a higher level. Drained land helped satisfy the small country’s hunger for more land for cultivation and habitation. Other windmills were used as a source of industrial power: to grind grain, husk barley, press oil from crushed seed, saw timber, grind oak bark for tanning, and make flower, paper, gunpowder, mustard, snuff, pepper – the list is endless.

Wind Mill Powered Flour Mill, the Netherlands

Windmills were used in the Netherlands from at least the fourteenth century until well into the nineteenth century. Around 1850 some nine thousand were still at work, the largest number that ever existed. Soon afterwards, when it was recognised that energy generated by steam was much more efficient and reliable than wind power, which can be fickle, the number began to decrease, at first slowly, then more rapidly. At the century’s close windmills by the thousand had been abandoned, demolished or aloud to decay. Introduction early in the twentieth century of power generated by internal combustion engines and electricity ensured their demise.

Long abandoned windmill near our former home in Lancashire

Only in the 1920s, when less than a thousand windmills remained, did the pendulum begin to swing slowly in the other direction. At that time, enlightened Dutch private citizens and government ministers realised that although new sources of energy may have made traditional windmills superfluous for drainage or industrial purposes, the complete disappearance of these structures from the Dutch landscape would be an irreparable historical and cultural loss. Plans were made and implemented to renovate and provide for the upkeep of the relatively few windmills that had managed to survive. The cause was helped by ordinances forbidding their further destruction.

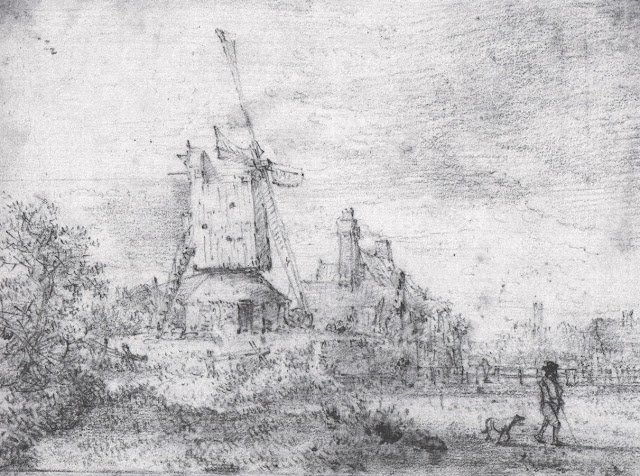

Thanks to the efforts of the wise Dutch who fought successfully to preserve a precious part of their country’s heritage several types of old windmills can be enjoyed and studied in the Netherlands today. Ruisdael’s paintings provide an additional source of information about them. He chose them as the main subject for three of a group of nine black chalk drawings, all similar in size and style. One is illustrated below.

Windmill at the Edge of a Village with a Man and a Dog c1640

They probably belonged to a sketchbook he used in about 1646 for studies of the countryside near his native city of Haarlem. Spaciousness, luminosity, and the airy atmosphere of the countryside, mainly achieved with sensitive stippled touches of chalk, are stressed in these sketches, and differences between the mills, adjacent buildings, earth and sky are slurred over. These qualities link them more closely to landscapes by artists of the previous generation, such as Jan van Goyen and Jacob’s uncle Salomon van Ruisdael, than to Ruisdael’s own early paintings.

Jan van Goyen: Dutch Landscape

The type of windmill seen in these drawings is a post mill (standerdmolen) that had been used in the Netherlands since late medieval times. It was mainly employed for grinding grain. A pen drawing of a group of them by Claes Jansz Visscher gives a clear view of their elements.

Claes Jansz Visscher: A Group of Windmills c1608

They were mounted on a pyramid-like stationary base, which, as Ruisdael’s sketches show, could be converted into a shed or cottage that doubled as work space and/or living quarters. The entire upper structure, where the grinding took place, could be rotated on its base into the wind by a pole at the back called a tail pole. A ladder gave the miller access to his mill.

Among the most impressive seventeenth-century Dutch views of a post mill is one by Rembrandt, his only painting to give great prominence to a mill. Datable to the 1640s, Rembrandt’s mill painting was produced when Ruisdael created the works discussed here. It is not known whether he ever caught a glimpse of Rembrandt’s mill painting, but it seems he never attempted to emulate its delegate, yet highly dramatic effect of light and shadow, which invokes deep emotional associations.

Rembrandt: The Mill 1640s

A type of mill that evolved from the post mill was the hollow-post mill (wipmolen), which was mainly used for drainage. Like its close relative, it had a revolving upper part and a stationary base. It was also equipped with a tail pole and ladder. Its upper part had become relatively small and its lower part relatively large. The upper part now accommodated only machinery and a long upright shaft that extended vertically through a hollow post from the top to the bottom. At the base the shaft helped run machinery either for grinding or, more often, when attached to a wheel, for scooping water. The machinery in the stationary base occupied quite a bit of space, but there was usually enough room to provide living quarters for the miller and his family.

Dutch Hollow Post Mill

In Ruisdael’s quick black chalk sketch of two post mills near the edge of a town, dateable to about 1640, the massively solid form of the prominent mill receives greater emphasis than in previous windmills depicted by Ruisdael, and there is no trace of their quasi-pointillist technique. At the very beginning of his career, perhaps, Jacob experimented with more than one way of working as he strove to obtain different landscape effects.

Close inspection of the mill in the painting shows that the disposition of the shadows on its base and upper structure is identical to that of the prominent mill in the drawing. The position and distinctive twist of the sails are also the same. Curiously, both show mills with three sails, not the usual four, and both lack the same sail. The cottages on the left and the fences near the small canal are congruent, as is the general lay of the land. There are some differences: in the painting the artist gives the mill a village setting by substituting a church for the second mill, introduces an old solitary traveller with a dog, adds light and dark contrasts, and makes some changes in the distant prospect.

The painting probably predates the more tightly knit and dramatic Landscape with a Windmill (above). It's mother-of-pearl pink, blue, grey, and white streaky clouds and late-afternoon sky distinctly recall effects achieved by Jacob’s uncle Salomon van Ruisdael. The similarity indicates that Jacob knew Salomon’s work well and lends support to the hypothesis that his uncle was one of his teachers. However, the dense massing on the right of the cottage - trees, gate and fence - all dominated by the windmill, is without precedent.

Datable to about 1650, Evening Landscape: a Windmill by a Stream is an impressive, large variation on Landscape with a Windmill. It shows the strides the young Ruisdael made over the course of a few years. The Farmstead and post mill are set back, crowns of high oaks have a new importance, the distant view, which now includes an extensive linen-bleaching field, is considerably expanded, and reflections of evening light fall into the lower and middle zones, creating a more ample and freer sense of space. Evident changes are also seen in the heightened sky and the introduction of emphatic thick clouds that billow above and extend over the landscape.

John Constable: Windmill on Beverly Brook 1829

As mentioned earlier, the English Artist John Constable greatly admired Ruisdael’s work. At the time of his death in 1837, Constable’s art collection included three paintings and four etchings by Ruisdael, as well as four of his own copies of Jacob’s work. It is not astonishing that Constable should have a great fondness for windmills when we learn that in his youth he worked in his father’s mills. Mills were in Constable’s blood. His younger brother Abram recognised the attachment and was proud of it: “When I look at a mill painted by John”, he wrote, “I see that it will go round, which is not always the case with those by other artists.”

Jacob van Ruisdael: Two Windmills on the Bank of a River c1655

During the 1650s Ruisdael produced a group of unpretentious, small paintings – often on wooden panels – of plain Dutch scenes that appear to be hardly modified excerpts from nature. Their subjects are simple motifs: a conspicuous hollow-post windmill (as above) or a modest farm on a riverbank, a glimpse of a beach seen from a high dune, or merely the scrubby dunes themselves. They are characterised by their fresh, sketchlike quality, a relatively bright palette, and a tendency to open up and lighten space, markedly different from the monumental effects of some of his larger landscapes done during the same decade.

The windmill seen in the distance here can be called a common tower mill, a type that took various forms and as such acquired different Dutch names. Like post mills, they had been found in the Low Countries since late medieval times and gained popularity during the seventeenth century. Usually larger than post mills, tower mills could be octagonal timber structures set on a stage secured on an elevated foundation, or set on an octagonal base directly on the ground.

Dirck Everson Lons: Leather Tanning Windmill 1631

The cap (that is, top) of these mills carried their sails. Only the caps rotated to turn the sails into the wind. They were turned by a wooden mechanism (tail poles) attached to the cap and extended to the stage or ground. Cylindrical tower mills were also used. They were usually constructed of brick and masonry, materials that were far less vulnerable than timber to dampness and other vagaries of Dutch weather.

Though Ruisdael’s small paintings of the 1650s often appear to be done from life, there is no reason to believe he ever set up his easel outdoors and painted from nature. From the beginning he followed the general practice of seventeenth-century Dutch artists: drawings were done from and then, on occasion, used as studies for pictures worked up at home or in the studio.

Ruisdael was not the kind who made precise squared, indented preliminary drawings for his own paintings and etchings. In fact only one of his drawings is related to his very small production of merely thirteen etchings (none of which include wind- or water mills). Why he stopped etching in the early or mid-1650s, after creating some of the most clever etchings produced in seventeenth-century Holland, remains unknown.

Jacob van Ruisdael: The Three Oaks

Apart from increases in the height of the trees on the right and the height of the bank on which the tower mill stands, the introduction of shrubbery on the left, and an enhanced sky, there is virtually a one-to-one connection between the painting and the drawing. A close look at the chalk sketch shows that it is clearly inscribed in the lower left corner in brown ink: J. Ruysdael.

The signature is not in Jacob van Ruisdael’s hand. It was probably written by an unknown dealer or collector.

The recent history of the drawing is quite intriguing. In 2002, one year after it was catalogued as presumably lost in World War II, it resurfaced. Revelations about its post war history could serve without embellishment as the plot of a thriller. During the war it and about fifteen hundred other works were hidden in a castle in Nazi Germany until Invading Soviet troops stole the cache. Later, the works were acquired by the KGB and deposited in the National Museum in Baku, Azerbaijan,

National Museum in Baku, Azerbaijan,

where they were stolen again in 1993. In 1997 they were in the possession of a former Japanese wrestler who attempted to sell them in Tokyo to pay for a kidney transplant. Later in the same year, part of the hoard was found in a closet and under a bed in a Brooklyn apartment. In July 2002, U.S. officials finally returned the Ruisdael drawing to Bremen, where it belonged.

Jacob van Ruisdael: Landscape with Two Windmills - mid-1650s

In 1831 John Constable painted a copy of the picture, which was still in his possession at the time of his death in 1837.

The silhouette of the large church on the horizon bears some resemblance to St. Bavokerk, the principle church of Haarlem, but the lay of the land is quite unlike the topography of Ruisdael’s native city.

St. Bavokerk Church, Haarlem

The copy included a horseman and boy on the right, which pigment analysis later showed to be additions to Ruisdael’s effort. They were removed during conservation treatment in 1997.

Jacob van Ruisdael: Windmill near a River - mid-1650s

The composition, handling and almost square format of this oil on panel painting are similar to those of Landscape with Two Windmills and their dimensions are virtually identical, suggesting that Ruysdael painted both around the same time. Ruins seen in the distance of Windmill near a River are the remains of the large Romanesque Egmond Abbey.

Jacob van Ruisdael: High Bridge over a Sluice c1655-1660

Various attempts to identify the precise location of the bridge here were unsuccessful until 1998, when L.D. Couprie pinpointed it. He recognised that the break in the middle of the high bridge’s railing indicated that it was an oorgatbrug, a fairly common type in the Netherlands during the seventeenth century. These stationary bridges had narrow gaps across the middle of their decks that were covered with loose planks. When a vessel with a tall mast needed to pass through, the planks were removed.

None of Ruisdael’s earlier paintings of windmills hint at the supreme qualities of his most famous work, Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede. The essence of the work’s pictorial beauty is the firm cohesion of forms that harmonise the dominant vertical mass of the grain mill’s cylindrical body rising over the town with the high clouded sky, the breadth of the land and the broad expanse of the river. The bond between the upper and lower parts of the landscape is strengthened by the interplay between the clouds and the country side. Not only does the direction of the arms of the huge mill relate to the direction of the thick clouds, but also every point on the ground and on the water is subtly connected to a corresponding spot in the vault of the heavy grey sky. Rhythmic tension is created between near and far by the strong emphasis on both the close and distant views, and by the contrasts between light and shadow that work together with the intensified concentration of mass and space.

Ruisdael was equally attentive to man-made contrivances, as can be scene in a close-up view of the mill’s sails. In Ruisdael’s time, there could have been few Dutchmen who did not know that the sails of a windmill in their part of the world move counter-clockwise. Thus, when spars are used, they are placed either in the middle of the the sails’ frames or forward toward their leading edges. If placed aft they produce shudder, which can be fierce or even shattering. The detailed view of Ruisdael”s mill shows the spars in a usable position, forward toward the sails’ leading edges.

Rembrandt van Rijn: The Star, or The Little Stink Mill 1641

It is noteworthy that Rembrandt’s impressive 1641 etching The Star, or The Little Stink Mill shows a mirror image of the mill. (The windmill that Rembrandt etched was owned by the Leathermakers Guild, which used it for softening tanned leather with cod-liver oil, a process that produced a pervasive stench, hence its nickname.) Counter clockwise rotation of the mill’s sails with their spars in the aft position, as seen in impressions of Rembrandt’s print, would produce violent shudder. Apparently mature Rembrandt, a miller’s son who must have learned about windmills as a lad, was not troubled by his mirror view.

Wijk bij Duurstede

Since the nineteenth century it has been known that Jacob’s painting offers a view of Wijk bij Duurstede, a small town situated about 20 km from Utrecht at a spot where the Neder Rijn (lower Rhine) divides into the Lek river and the Kromme Rijn (Crooked Rhine). Until the middle of the 20th century it was assumed that Ruisdael painted a mill that still existed in the town, but it has been established that this assumption was wrong. The existing windmill is a gate mill with a square base and it lies north of the town. The one Ruisdael painted had a round base and was situated south of the town.

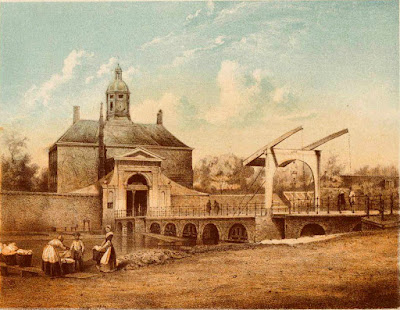

The Town’s Women’s Gate, which is not included in Ruisdael’s painting, was a short distance down to the right. An anonymous eighteenth-century drawing of the mill clearly shows the gate.

Women's Gate (detail)

Two of the buildings Ruisdael depicted can be identified. To the left of the mill the late medieval castle of Wijk is clearly distinguishable.

Medieval Castle of Wijk

On the extreme right the squat tower of the Church of St. John the Baptist can be seen.

Church of St. John the Baptist, Wijk bij Duurstede, Holland

Ruisdael began to paint panoramas of the distinctive skyline of Haarlem with its nearby fields and linen-bleaching grounds in the 1660s and in the following decade the spectacle of towering clouds and vast expanses of land. In this period his other scenes of the Netherlands in its various aspects – particularly fertile plains, the sea and shore, the woods, as well as imaginary views - acquire wider prospects and awe-inspiring skies. Several of Ruisdael’s paintings of mills show that they often operated in bitterly cold conditions, but neither Ruisdael nor other Dutch painters ever showed them subjected to gale forces or blizzards.

Jacob van Ruisdael: Winter Landscape late 1660s

Emphasis on human figures in the fore- and middle ground and little more than a glimpse of the tiny houses on the distant horizon place the painting in the late 1660s. It earned the highest praise from Ruisdael’s early critics. Gustav Waagen, a leading authority on Western painting said: “The feeling of winter is here expressed with more truth than I have ever seen”.

John Constable also was full of admiration for this work. In 1832 he painted a copy of it that was still in his possession when he died in 1837.

John Constable: Winter Landscape with Two Windmills 1832

His copy is an exceptionally faithful one, apart from the dog he included on the left. It was inserted to help differentiate the copy from the original.

Constable said of his work: This picture represents an approaching thaw. The ground is covered with snow, and the trees are still white. But there are two windmills near the centre. The one has the sails furled, and is turned in the direction from which the wind blew when the mill left off work. The other has the canvas on the poles, and is turned the other way, which indicates a change in the wind. The clouds are opening in that direction, which appears by the glow in the sky to be the south (the suns winter habitation in our hemisphere), and this change will produce a thaw before morning. The concurrence of these circumstances shows that Ruisdael understood what he was painting.

Other Ruisdael paintings with windmills are more expansive than these.

They also eliminate its emphatic foreground emphasis.

The painting shows unpretentious houses clustered around a tower mill set in the middle distance. Only the wisp of smoke rising from the house’s chimney and a few tiny scattered figures signal human presence. With exquisite subtlety the picture typifies the almost monotonous grey atmosphere of a winter day. Here the winter mood is tender rather than ominous.

Ruisdael’s powers of observation did not slacken in his late period. Anyone with experience of fruit-growing trees in temperate climates will recognise that the large snow-covered tree is an old apple tree with the shoots following pruning in the previous spring clearly indicated.

Logs and long timber beams on the right side of a winterscape indicate that the high post mill, erected on what appears to be the snow-covered remains of an ancient brick fortification, is a sawmill. The strong horizontal composition and concentration of prominent elements of the wintry landscape in the middle ground are uncommon in Ruisdael’s work. Attempts to identify the manor house with scaffolding have been unsuccessful. It may very well be the artist’s invention.

Eugène Delacroix once said of Ruisdale’s winterscape that they appeared to be summits of art because their art is completely concealed. By contrast he considered that the works of Watteau and Rubens showed that they were ‘too much the artists’.

An exceptional sky is seen in this painting, where Ruisdael shows rays of light emanating from the sun’s orb. Equally rare in his work is the tiny anecdotal detail on the wide expanse of the frozen river of small koly players waiting for their companion to tie his skates The long snow-covered beams and shorter logs near the big shed adjacent to the prominent windmill indicate that it is a sawmill.

Jacob van Ruisdael: View of a Windmill near a Town Moat, early 1650s

As seen in the distance here, mills in the seventeenth-century were often built on the bulwarks of town and city walls. A high position, of course, enables a mill’s sails to capture more wind. In this painting Ruisdael shows as much interest in the meticulously painted, old brick supports of the makeshift bridge as he does in the picturesque background view, a common note in his work. From the very beginning he seems to have taken as much pleasure in painting ample displays of bricks, mortar and masonry as he did in depicting superabundant foliage, without boring himself or his viewer.

Above is an etched view of a post mill named the Little Young Lady on a rampart on the left bank of the River Amster near Amsterdam’s Blue Bridge that is surely based on an untraceable drawing by Ruisdael. It belongs to a set of six etchings that the printmaker Abraham Booteling made in about 1664-65 after Ruisdael’s drawings of areas in Amsterdam.

Jacob van Ruisdael: View of the Amstel Bridge c1663

This is Ruisdael's title page drawing for the set, which includes views of the city during the course of its great expansion in the early 1660s. Ruisdael’s drawing depicts a view of Amsterdam looking south from a spot on the east bank of the new Inner Amstel. On the left of the drawing is the huge post mill called De Gooyer, its height of 44.4 metres distinguishing it as one of the tallest in the Netherlands. Left of this is the enormous arched stone Amster Bridge, completed in 1663, that linked the new town walls and handled a large part of the city’s traffic. Beyond the bridge are three tower sawmills and the post mill called the Green Mill.

Jacob van Ruisdael: View of St. Anthony's Gate at Amsterdam c1663

We know of one resident who was well acquainted with this bridge: Rembrandt van Rign. From 1639 until 1658 he resided at Amsterdam in a great house just a few minutes walk from the gate, which he passed through on frequent sketching trips to the countryside beyond. In regard to suggested inaccuracies in the depiction of the gate, other Amsterdam landmarks justify the drawing’s title. The charming tower and spire of the South Church are recognizable and correctly placed. So are, on the right side, the large tower windmill called the Horseman and the bunkerlike buttress with its two towers.

Jacob van Ruisdael: Panoramic View of the River Amstel c1675-81

The exceptionally extensive bird’s eye view may have been made from the tower at the Peacock Garden, a popular seventeenth-century excursion destination down the Amstel. Emphasis has been given to the foliage on the trees, the windmills and other structures in the fore’ and middle grounds. The distant view has only been lightly sketched, but it shows enough of the city’s principal structures to make identification possible. Amsterdam is portrayed here after the completion of the new city wall.

The large building with a domed tower left of centre on the horizon is the monumental New Town Hall (5), today the Royal Palace on the Dam, the city’s principal square.

The drawing served as a preliminary study for Ruisdael’s two similar but not identical paintings of the city.

Comparison of the drawing with both versions makes clear that the unusual cropped tree crowns that run along the sheet’s foreground are the result of its lower part having been considerably cut. We can only guess if the drawing ever included the towering cloud-filled aerial zones of both paintings. If it did, the height of the drawing was originally about two-thirds greater than it is today. The dark grey wash in the upper right part of the drawing is almost certainly a later addition by another hand. Perhaps it indicates that something untoward happened above it and then was cut away.

A notable feature in both painted versions is the very high cloud on the right, which meteorologists readily recognise as a cumulonimbus cloud. Wisps of icy particles account for the frizzy top. Apparently, this is the only accurate portrayal of this type of cloud in seventeenth-century Dutch art. Also to the right is a gigantic cloud not found in nature. A meteorologist has baptized it pseudocumulus colis Ruisdael.

Jacob van Ruisdael: Two Undershot Water Mills with an Open Sluice 1653

No one knows how a particular water mill looked in Ruisdael’s time, and there is ample evidence that he often selected, rearranged and invented elements of his landscapes to suit his needs. Thus, attempts to determine the precise locations of his water mill pictures have proven futile. The painting’s major undershot mill, with its half-timbered and cob façade construction, the beams and vertical plank gable, is a typical example of the region’s style of architecture.

Engraved detail from Two Undershot Water Mills

Dates, as well as locations are problematic in Ruisdael’s work. 1649 is the last year he is known to have dated a work on paper. But one way of establishing rough dates is to consider the way an artist handles paint during different periods of his career. A telling example of this point is offered by juxtaposing a close view of the weeds, reeds, grasses and other objects on the bank in the foreground of Two Undershot Water Mills with a similar passage in the foreground of Ruisdael’s Windmill at Wijk dij Duurstede, which must have been painted at least fifteen years later.

Detail from Two Undershot Water Mills

In the work of 1653 details are scrupulously transcribed. The impression of flickering light playing over the tangled thicket is created by the different hues of green and warm brown used to delineate almost every single leaf and blade of grass. Highlights are in paint that is singularly dry. Contrasts between light and dark on the dressed stones are intense, yet shadows remain transparent.

As for the weeds and pilings here, less is more. Ruisdael has abandoned his early passion for detail. Reeds have been summarily drawn with swift, crisp and sometimes razor-sharp strokes of his brush dipped in paint that almost has the viscosity of ink. Economy and sureness of touch are now the watchwords.

Detail from Windmill at Wijk

The mill on the right here is severely cropped: only the edge of its rotting wall, its thatched roof and a section of one of its stationary water wheels are visible. The cascade of water rushing from the broad open sluice is among the artists first successful attempts at portraying a powerful torrent seething with foam.

Detail from Two Undershot Water Mills with an Open Sluice 1653

The trees in this painting are as impressive as the mills and the rushing torrent, especially the great towering oak that seems to embody the vital forces of growth in nature. On the far left there is a tiny detail that could have served as the artist’s signature had he not signed the work. It is the lone traveller with his white hound. A solitary man and his dog, often not really noticed are frequently included in Ruisdael’s landscapes. The man in this picture is more conspicuous than most. The red of his jacket is the sole spot of intense colour.

It is the lone traveller with his white hound. A solitary man and his dog, often not really noticed are frequently included in Ruisdael’s landscapes. The man in this picture is more conspicuous than most. The red of his jacket is the sole spot of intense colour.

At first sight, this watermill appears quite similar to the one just discussed, but there are significant differences. In this one, there is a much closer view of the sluice’s very long foremost beam and of the wooden posts and planks beneath it, as well as the large, half-timbered mill capped by a thatched gable roof. The landscape plays a less significant role here and its foreground differs considerably. In addition the mill on the right has become a ruin with a defunct water wheel.

But which picture was painted first? Arguably, the one above because there Ruisdael achieves a more serene balance between the water mills and their rich natural setting. Another consideration is the treatment in each work of the torrent cascading from the open sluice and its agitated tail water as it rushes downstream. Both are equally convincing.

Jacob van Ruisdael: Two Undershot Water Mills with an Open Sluice c1651-52

This cannot be said of the water rushing through the open sluice of a related painting. The cascading water here bears a resemblance to cotton batting and its boiling foam ends too abruptly. Greater accuracy in the portrayal of the tail water in the previous paintings implies an understanding of the action of turbulent water. This suggests that this painting predates the other two works.

Notable in the previous painting and the variant on it here is the different state of preservation of the right-hand mills. But it would be wrong to rely on their relative deterioration to establish their chronology. Ruisdael’s ruined mills, like their landscape settings, are concoctions of his imagination, not faithful copies of what he saw before his eyes.

Jean-Jacques de Boissieu produced an etching after Ruisdael’s painting in 1782. The etching is very close to the original, but it extends farther to the right, where it depicts two artists sketching, omits the sheep and shows three workmen instead of one on the sluice. Apparently, the changes were Boissieu's own inventions.

In this painting only the masonry and brick foundations of water mills remain. The huge, ancient blasted oak with its twisted roots clawing into the turf on what is left of a mill stresses the age of the ruins. Ruisdael seems to want us to contemplate the many decades that had to pass for it to take root in this place and become an enormous battered tree.

Sharp contrast between the remains of the mill run, the crumbling ruined building in the middle ground, the broad sheet of rushing water and the towering half-dead tree on the one hand and the force of nature’s proliferation on the other suggests that the painting has an allegorical intent. The combination of conspicuous ruins, moving water and dying or dead trees may very well allude to the transience of life and the ultimate futility of all human endeavours – a common theme in seventeenth-century Dutch art – while nature’s luxuriant growth offers a promise of hope and renewed life.

Jacob van Ruisdael: Thatch-RoofedHouse with an Undershot Water Mill c1653

When John Constable saw this painting in 1829, he wrote to a friend: ‘I have seen an affecting picture this morning by Ruisdael. It haunts my mind and clings to my heart – and has stood between me & you while I am now talking to you. It is a watermill. A man & boy are cutting rushes in the running stream (in the “tail water”) - the whole so true clear & fresh - & as brisk as champagne – a shower has not long passed. It showed Ruisdael’s aptitude in landscape.

Jacob van Ruisdael: An Overshot Water Mill c1650-55

Although the mill is in rather deep shadow, it shows unmistakable similarities to the drawing above.

In this black chalk drawing we see a close side view of the mill pictured above. It is notable for its vigorous, yet meticulous differentiation of foliage and convincing depiction of rushing and still water.

These features are not immediately apparent in the painting based on the sketch. Although the latter has darkened considerably, detailed inspection reveals striking similarities.

This sketch, similar to the last one, was done by Ruisdael’s pupil, Meindert Hobbema. His handling of wash looks blotchy compared to that of his teacher and his treatment of the dark and middle tones in the foliage is more distinctive. The landscape and details of the mill’s construction differ as well. Notable are the distinctions between the two large water wheels. Ruisdael’s wheel has a simple large hub and four spokes. Hobbema’s has a huge square hub with eight sturdy spokes.

An outstanding work that includes it as the principle subject is Hobbema’s painting pictured above. This work and others by him support his unshakable reputation as an outstanding painter of watermills. Indeed, the name that first comes to mind when Dutch landscapes with water mills are mentioned is Hobbema’s. But it is well to recall that his teacher made masterpieces that had water mills as their central focus before the pupil held a brush in his hand.

Jacob van Ruisdael: Overshot Water Mill and a Millpond c1655-60

The painting’s state of preservation is not good. It has dark patches that are difficult to discern. The wide expanse of the millpond that extends across the foreground and the strong contrast between the main motif and the solid mass of the tree-covered hill behind it, with an open vista stretching to the horizon, suggest that it was painted about 1655-60.

A very unusual close view of the back side of this water mill, executed in black chalk and grey wash, but unlike the other three drawings, it has touches of pen and black ink.

The drawing above served as a working drawing for this painting that appeared in a 1983 sale as an unpublished work. After it appeared, removal of its old discoloured varnish revealed numerous scattered paint losses in the sky and abrasion in the original paint surface of the foliage.

The painting is one of Ruisdael’s rare dated pictures of the 1660s. Though the last digit of the date is no longer legible, copies or variants after it by or ascribed to Hobbema lend support to the date of 1661 read on the original by earlier specialists.

Meindert Hobbema: The Travellers 166(?)

A Hobbema copy, entitled The Travellers, greatly enlarges the original’s dimensions, makes changes in the foreground and adds two horsemen on the road by another hand.

The central focus here is a large, snow-covered inoperative water mill and sluice next to a frozen millpond. Snow blankets the landscape and the distant village. A break in the heavy brooding clouds suggests the sky may soon lighten.

Jacob van Ruisdael: Overshot Water Mill in a Mountainous Landscape 1670s

Jacob van Ruisdael: Three Undershot Water Mills with Washerwomen at the Foot of a High Hill c1675

A very badly damaged painting, particularly in the dark areas, but enough can be seen of the miniature treatment of the three large mills to place it about 1675. It is a pity the painting has suffered so much. Without a magnifying glass, it is difficult to make out the activities of the working washerwomen and their little children in the foreground’s light area.

The mills in the painting above are closely related to those in this black chalk and grey wash drawing datable to about the same time, but any solid connection between the drawing and the painting remains tentative.

The paint film here is generally, and in some places, badly worn. The calm scene and insignificant role of the clouds are unusual for Ruisdael, but in its intact passages the touch speaks for Jacob’s hand, particularly in the large half-timbered mill, its reflection and the grasses. Datable to Ruisdael’s last years, it offers a distinct premonition of eighteenth-century pastoral landscapes.

Jacob van Ruisdael

1629 - 1682

Links to more posts on painting:

No comments:

Post a Comment